Over the past three-plus decades I've been in the industry, I've always appreciated what customers and colleagues bring to the table when it comes to music. There are those albums and tracks that are timeless and demand play after play, and then there are demos that causes you to grasp your wallet as if to say, "I'll take the damn amp, just stop playing that album!" Where that divide stops is when someone like Ron, my friend and former colleague from my local audio shop days, would spin a disc to woo a customer. His picks were streetwise and hip, and always on the cutting edge. He was (and remains) one of my muses in finding a great album to own and cherish.

The working bond my sharply dressed friend and I shared was very unique. We shared the sales floor at the local dealer we worked at during the daytime hours and at a club he managed (and at which I briefly deejayed) in the evenings. We'd also hang out at some of the popular clubs in Chicago, such as Sonotheque or Cairo, with the scene (and music) doing its smooth talk, only to head home to our respective pads and get ready for the Sunday ritual, too inebriated to ask the DJ what he was playing in hopes of grabbing a copy the next day.

Despite the usual hangover associated with the previous night's debauchery, Sundays were a time of long walks and record shopping. It always began with a trip to the Hamburger King, an unassuming place near Wrigley Field owned by Sonia, a tough albeit charming Korean woman whose menu was the first word in dive-diner fusion. We avoided the usual bacon and eggs or other heartburn-inducing fare and went for the special Korean and Asian breakfasts and soups, including a full-on calorie-loaded plate of teriyaki steak and eggs, complete with sesame-seeded dark-glazed thin strips of beef giving way to steamed rice and brown gravy. Black coffee, naturally, and no juice, please.

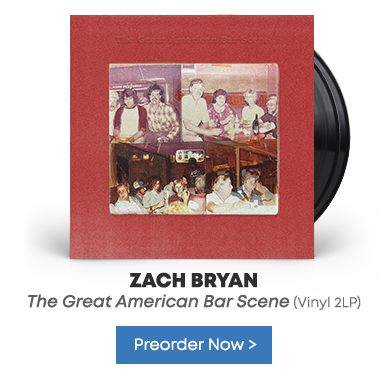

To burn off the calories, we'd saunter over to a few well-known record stores of the day that dotted the Lincoln Park streetscapes: Dr. Wax, Gramophone, and later, Tower Records, newly opened up in a building that once was the storefront for the greatest late-night bowl of matzo ball soup, the Belden. The visits were always the same, each of us saying hello to the shop managers and staff, some recognizing us from our frequent stop-ins, others just grunting as if to say, "damn browsers." And then, the digging began. Multiple copies of new singles, extended mixes, club hits – many from artists I had no clue about. An occasional jazz record or compilation to whet the appetite, an odd folk album, a rock album of the day from the likes of the Smithereens, Marshall Crenshaw, Elvis Costello. And then, filed under "Acid Jazz," a two-record set of cuts from some guy named Guru. "Buy it," Ron said with a soft voice. "Why? Do you like it?," I asked. "Just BUY it," he instructed.

Guru (Keith Edward Elam (1961 – 2010)) was an innovative producer, rapper, and actor whose stage name was an acronym for Gifted Unlimited Rhymes Universal. His rise to fame as one half of the hip-hop duo Gang Starr was due to his lyrical rap that was more poetry than politic, a style that ushered in a roots scene that would later dissolve into jazz funk, neo soul, and jazz rap. The idea for his first solo effort, Guru's Jazzmatazz, Vol. 1, came from watching the DJs sampling jazz cuts. "I was noticing how a lot of cats were digging in the crates and sampling jazz breaks to make hip hop records," he said in a 2009 interview for Blues and Soul. "But while I thought that was cool, I wanted to take it to the next level and actually create a new genre by getting the actual dudes we were sampling into the studio to jam over hip hop beats with some of the top vocalists of the time. You know, the whole thing was experimental, but I knew it was an idea that would spawn some historic music."

The album preceded four sequels, each with star-power jazz artists playing alongside the talents of the moment. But none had the crackling fire and hipness Jazzmatazz Volume 1 sparked. As it happened, the acid jazz movement was fading along with the waning 20th century, and with it, newer styles and influences – nu jazz, trip hop, and chill – were soon in vogue. But Guru's legacy would remain as intact until his death at the age of 48 from multiple myeloma.

The album initially proved experimental, but on close inspection, it remains a borderline masterpiece. Whereas other collectives tried to reach mainstreamers via sometime-saccharine tones and all-too common beats – akin to background music in furniture stores – Guru's Jazzmatazz, Vol. 1 arrived with a soulfulness and chemistry that remains as powerful as the day it was released. Guru's wordsmithing, alongside legendary jazz and fusion stars like Lonnie Liston Smith, Roy Ayers, and Donald Byrd, comes across like the sounds of a colorful city music festival. And the presence of then-newcomers such as saxophonist Courtney Pine and guitarist Ronny Jordan (whose sound invoked that of Wes Montgomery) flexed the album's power. Plus, vocalists Carleen Anderson (stepdaughter to Bobby Byrd) and N'Dea Davenport (vocalist for the Brand New Heavies), and French rapper MC Solar provide ample counterpoint on tracks like "When You're Near" and "Le Bien, Le Mal (The Good, The Bad)."

As we trip through the second decade of the 21st century, Guru's Jazzmatazz, Vol. 1 seems as important as the day I picked up a copy – still as trippy as ever, and always spinning.

18th May 2020